Multiprocessing Experiments in Python

Introduction

As part of a course on Computer Architecture at university we were asked to evaluate the speedup dervied from using multiple CPU cores through multiprocessing in Python. This post details my findings. All experiments were conducted on MacBook 2020 with an M1 chip with 8 cores. The code is available on my GitHub.

I used the multiprocessing module in Python to control the number of processes and averaged the runtimes over 5 repetitions to smooth out the results as shown in the code below:

def pool_process(f, data, pool_size, num_repetitions=5, show_results=False):

"""

A function for timing a job that uses a pool of processes.

Args

----

f: function

A function that takes a single argumnet

data: iterable

An array of arguments on which f will be mapped

pool_size: int

Number of processes in the pool

num_repetitions: int, default 5

The number of times to call f for each pool size. The times are then averaged

show_results: Boolean, default False

Show the result from calling f

"""

total_time = 0

for i in range(num_repetitions):

tp1 = time.time()

# initialize the Pool

pool = Pool(processes=pool_size)

# map f to the data using the Pool of processes to do the work

result = pool.map(f, data)

# No more processes

pool.close()

# Wait for the pool processing to complete.

pool.join()

overall_time = time.time() - tp1

if show_results:

print("Results", result)

total_time += overall_time

avg_time = total_time / num_repetitions

print(f"Average time over {num_repetitions} runs: {avg_time}")

return avg_time

Checking for Prime Numbers

The first set of experiments involved the following check_prime function:

def check_prime(num, verbose=False):

t1 = time.time()

res = False

if num > 0:

# check for factors

for i in range(2, num):

if (num % i) == 0:

if verbose:

print(num,"is not a prime number")

print(i,"times",num//i,"is",num)

print("Time:", int(time.time()-t1))

break

else:

if verbose:

print(num,"is a prime number")

print("Time:", time.time()-t1)

res = True

# if input number is less than

# or equal to 1, it is not prime

return res

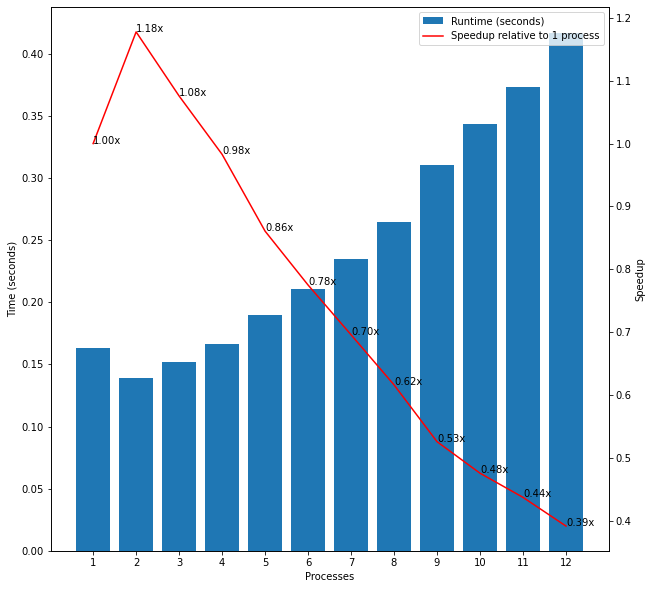

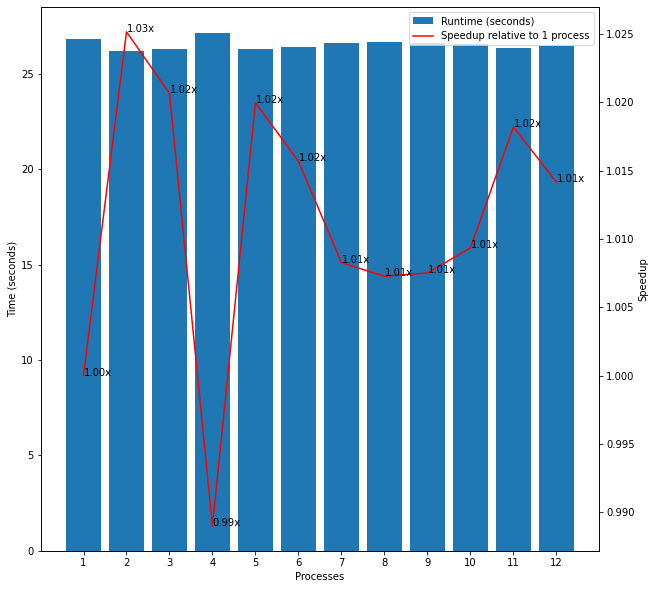

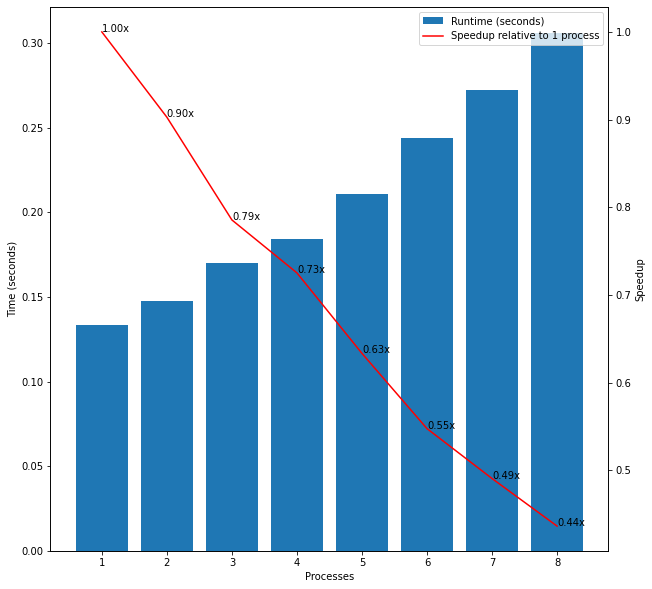

As my first test, I passed a list of all numbers from 0 to 100 as input to the check_prime function and timed how long it took to complete as the number of processes increased from 1 to 12. To my surprise, I found that the runtimes actually increased with the number of processes. For example, it took 0.13 secs to complete with 1 process but 0.17 secs with 4 processes (0.80x “speedup”) and 0.27 secs with 8 processes (0.50x “speedup”) as shown in the first plot in Figure 1. However, when I passed a list of numbers from 0 to 100,000 as input I found that the runtimes decreased as expected up to 8 processes as shown in the second plot in Figure 1. The speedup was not linearly proportional to the number of processes and instead the runtimes fell at a decreasing rate, however. Comparing these two results suggests that the overhead of additional processes may outweigh the benefits from parallelisation when the function can complete extremely quickly.

Figure 1: Initial Experiments

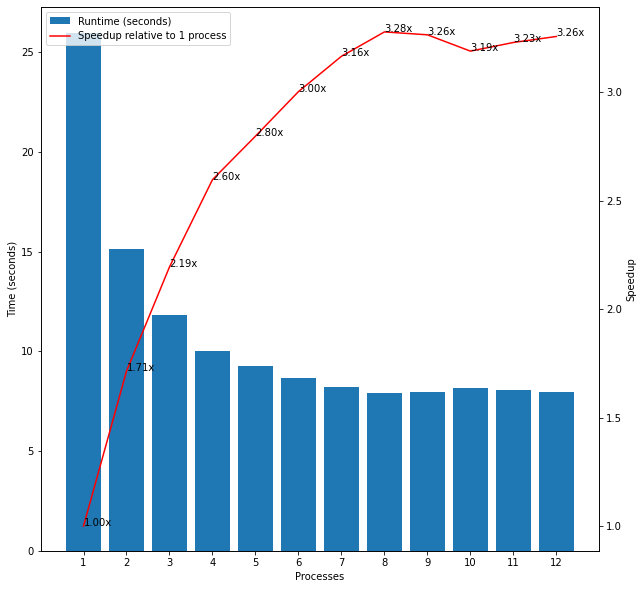

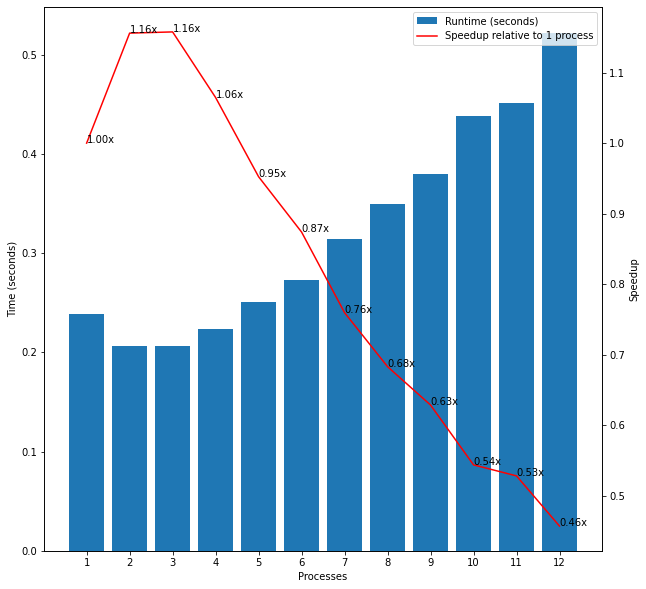

To further test this hypothesis, I used all of the even numbers from 0 to 1,000,000 as input because check_prime should complete very quickly for any even number no matter how large since it only needs to confirm that it divides evenly by 2 before breaking out of the for loop and returning False. Figure 2 shows that the speedups in this case seemed to combine elements of the previous two experiments. The runtime dropped from 0.37 secs for 1 process to 0.26 secs for 4 processes (1.42x speedup) but then started increasing again for each additional process with a runtime of 0.37 secs for 8 processes, for example (no speedup).

Figure 2: Even Numbers

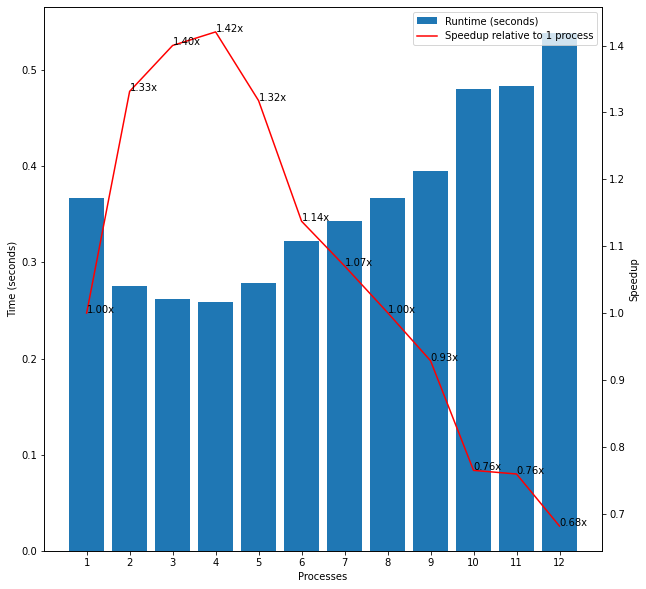

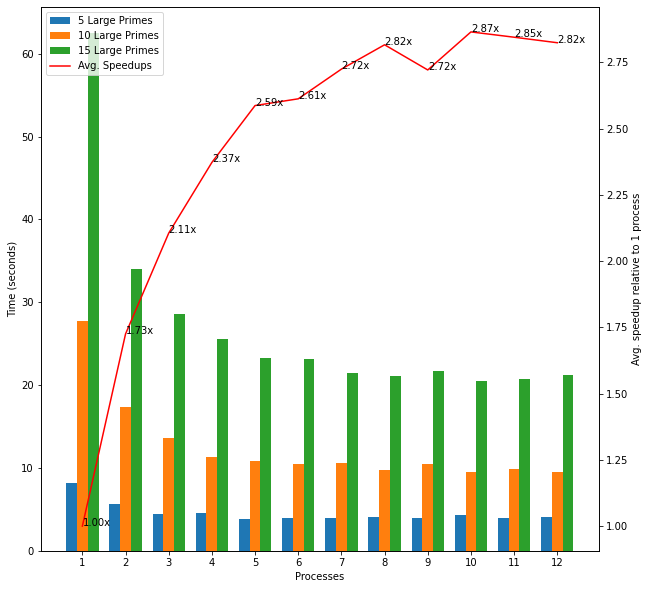

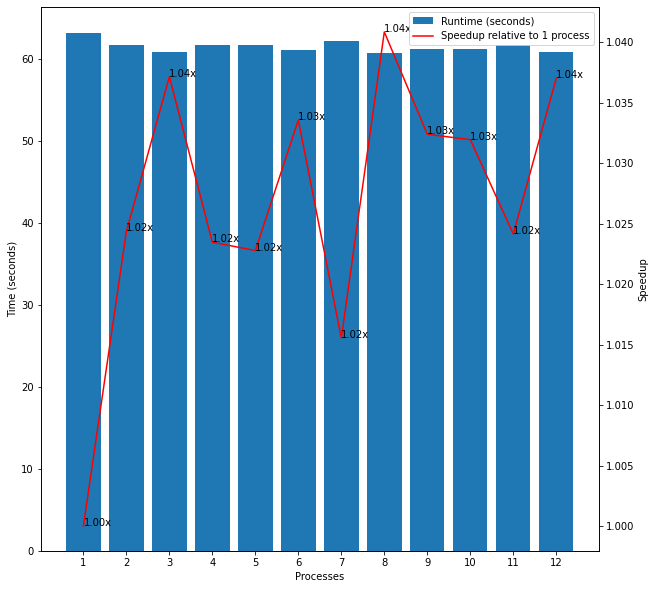

Next, I considered small lists of large prime numbers (at least 8 digits each). The biggest list had 15 such numbers. The average runtime across these inputs decreased up until 8 processes as we would expect but the rate of speedup again decreased as the number of processes increased. Comparing these results with the previous experiment confirms that even small lists of input can see significant benefits from multiprocessing in cases where execution is slow for each individual item.

Figure 3: Large Prime Numbers

However, when testing with an input of just one very large prime number, there were no speedup benefits from multiprocessing, presumably because the high workload could not be distributed across processes.

Figure 4: One Large Prime Number

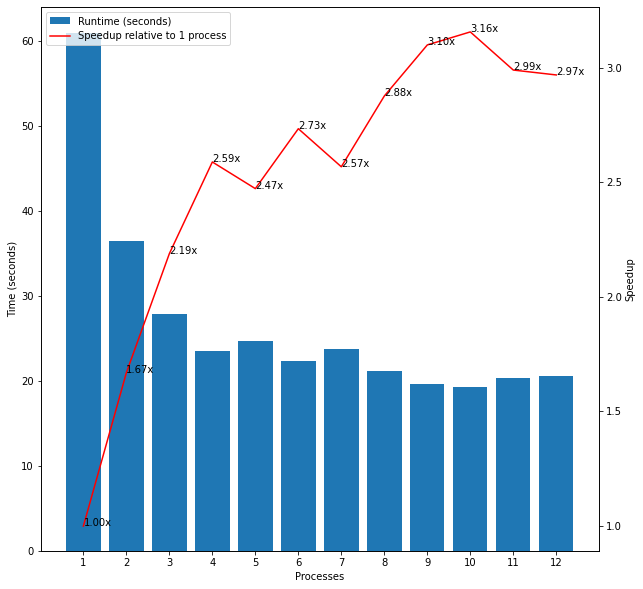

The next experiments I considered combined the above two groups. I created a list of all of the even numbers up to 1,000,000 plus fifteen large prime numbers. Interestingly, the first plot in Figure 5 shows that there was no speedup for parallelising this input and the overall runtimes were very similar to that when only passing the fifteen large primes as input to 1 process. I realised that this was likely because the large primes were at the end of the input and may therefore gather on one process while all of the other processes completed their much simpler workloads much more quickly and then sat idle. After shuffling the data, I found the expected speedup from in line with the other experiments as shown in the second plot in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Even Numbers and Large Prime Numbers

Overall, then, these results show that careful consideration must be given for whether the benefits of multiprocessing outweigh the overhead and this depends on factors such as the type of computation, the input, and how the workload is distributed. check_primes seems to be an embarrassingly parallel task and using Amdahl’s Law with the fraction of parallel processing as 1 and the number of cores as 8 would suggest that the maximum theoretical speedup should be 8 times. However, I never observed any result close to this and the largest observed speedup was just over 3x which illustrates the complexity and overhead of multiprocessing in practice.

I also ran all of the above experiments on up to 12 processes even though I have only 8 cores available on my laptop because I wanted to check whether trying to create more than 8 processes would actually reduce performance due to the overhead of managing unused or idle processes. In the cases where the runtimes decreased with the number of processes, there was some evidence that runtimes increased slightly for more than 8 processes but the differences were small compared with the overall speedup as shown in Figure 1. For the experiments that did not benefit from multiprocessing, the runtimes continued to increase steadily from 8 to 12 processes.

We might also intuitively think that the best performance would come from using all the available cores in our machine for a CPU intensive task. However, if we try to use all the cores in our machine for a multiprocessing task the performance may actually be worse because our job may be frequently interrupted by the OS needing to run other important processes. In this way, using N - 1 cores may actually result in better performance. In general, I did not find much evidence that runtimes were lower for 6 or 7 processes instead of 8.

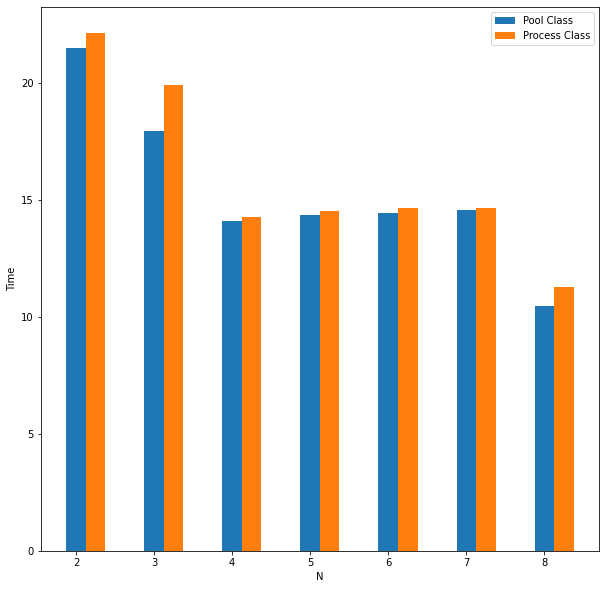

Pool vs. Process

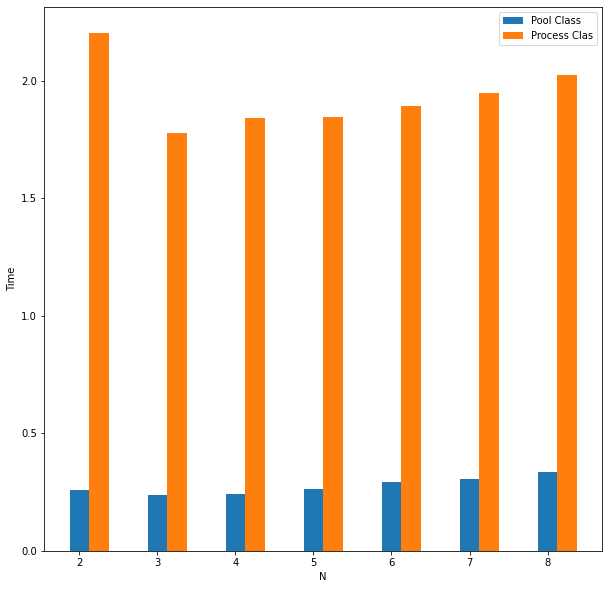

I also experimented with adjusting how the multiprocessing itself was performed in Python. For example, Python has two similar classes for multiprocessing. Pool is recommended for a large number of tasks that can execute rapidly because it can handle splitting the input data and only keeps those tasks that are under execution in memory. Process is more useful for a small number of tasks where each process is expected to take a long time to execute. Surprisingly, Pool performed slightly better than Process on an input of 8 large primes in all cases as the number of processes increased. However, Pool significantly outperformed Process on a list of all even numbers up to 1,000,000 as expected and sometimes ran almost 10 times faster.

Figure 6: Pool vs. Process

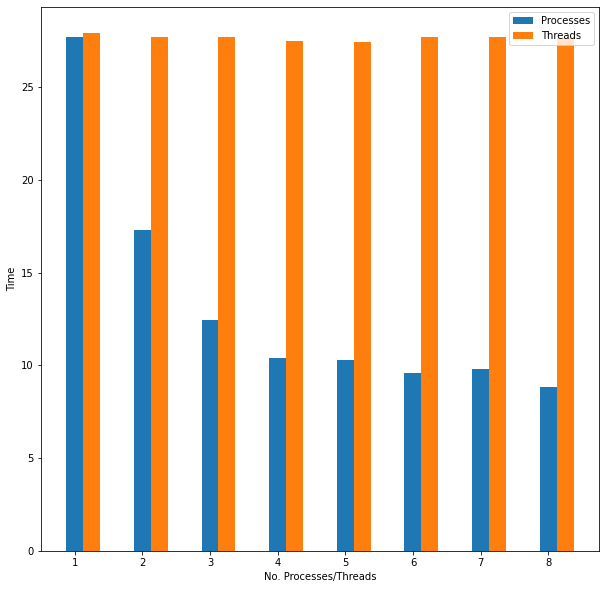

Multiprocessing is also recommended instead of multithreading for CPU-bound tasks like check_prime in Python because of the Global Interpreter Lock. I confirmed this by observing that there was no speedup from increasing the number of threads from 1 to 8 on an input of ten large primes in contrast to the speedup effect observed when using additional processes.

Figure 7: Using Threads

Estimating Pi

Moving on from checking for prime numbers, I next chose to estimate Pi because it can also be formulated as an embarrassingly parallel problem. The first algorithm I studied was a Monte Carlo (MC) estimation. Instead of passing lists of numbers as with check_prime, the input in this case is the number of samples in the estimation:

def pi_monte_carlo(n):

count = 0

radius = 1

for _ in range(n):

x = random.uniform(0, 1)

y = random.uniform(0, 1)

if math.sqrt(x**2 + y**2) < radius**2:

count += 1

return count

As in the previous example, I started with a small input of 100 samples and again found that multiprocessing did not provide any speedup presumably because the overhead outweighed the benefits of setting up extra processes.

Figure 8: Estimating Pi with n=100

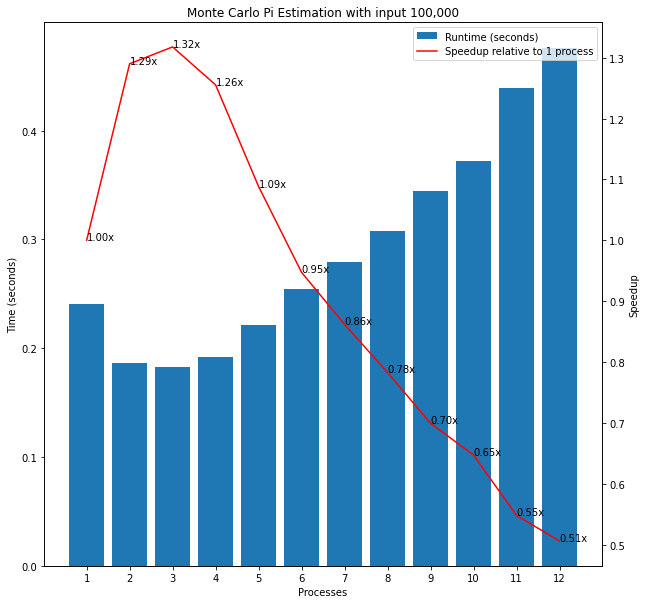

However, when I increased the samples to 100,000 I observed the runtimes would generally fall when 2 or 3 processes were used instead of 1 but then rise again and using 7 or 8 processes took longer overall than 1 process.

Figure 9: Estimating Pi with n=100,000

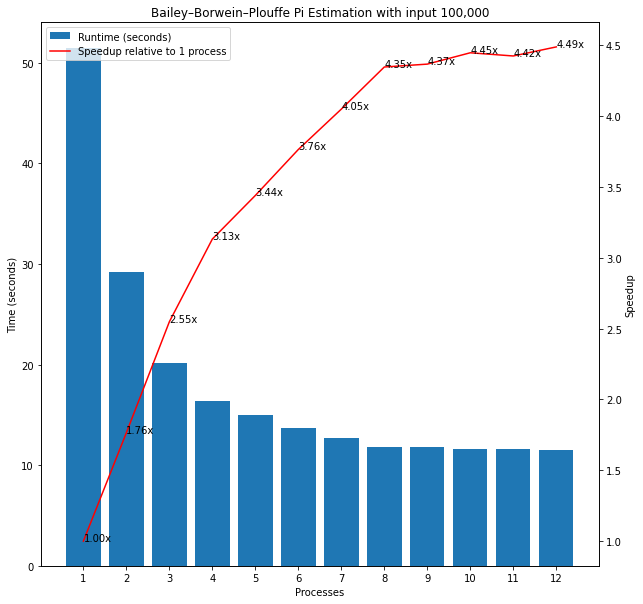

I then compared this method to a second interesting parallel algorithm to calculate Pi called the Bailey–Borwein–Plouffe (BBP) formula which independently calculates the nth digit of Pi. As with the MC method, this algorithm accepts a single integer input.

def pi_bbp(k):

term = 1/16**k * (4/(8*k+1) - 2/(8*k+4) - 1/(8*k+5) - 1/(8*k+6))

return term

When I passed 100,000 as input, the runtimes for the BBP algorithm continued to fall for up to 8 processes in contrast to the MC algorithm. However, the overall runtimes for the BBP algorithm were much higher than for MC. A subtle difference in the algorithms may explain this contrast despite the identical input. There is a for loop inside the MC algorithm so a single function call completes many of the requested 100,000 samples. By contrast, the BBP function is called separately 100,000 times and gives much more precise estimates of Pi and the overhead associated with this may explain the higher overall runtimes and the clearer benefits from multiprocessing in this latter case. These findings seem to confirm the above conclusions that the benefits of multiprocessing depend crucially on the algorithm used and the input passed and that this should always be tested empirically rather than relying on theory.

Figure 11: Bailey-Borwein-Plouffe vs. Monte Carlo Pi Estimation with n=100,000