Regex Performance in Theory and in Practice

Introduction

Most programmers are familiar with regular expressions (or regexes) which are frequently used to describe and parse text. It’s less commonly known that regexes can be represented by a fundamental computing concept known as a finite automaton. To determine whether a regex matches a string we can first translate the expression into its equivalent non-deterministic finite automaton (NFA). We can then use the string as input to the NFA and check whether the match succeeds. This process seems relatively straightforward but the algorithm used to check this match can have a dramatic impact on the performance of regexes in practice.

Backtracking vs. Thompson NFA

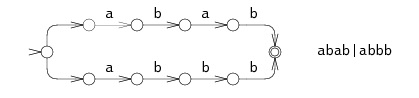

Russ Cox has a series of excellent blog posts which compare algorithms used to check whether a regex matches a string. The first is known as backtracking and involves trying all of the possible paths through the NFA one at a time. For example, consider the NFA in Figure 1 which represents the regex abab|abbb.

Figure 1: An NFA representing the regex abab|abbb. Source

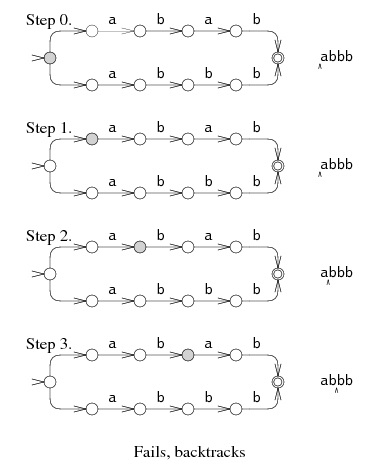

There are two possible paths through this NFA. If we want to check whether the string abbb matches this regex the algorithm will first try the top path and will get as far as the third node before the match fails and backtracks to the beginning of the NFA as shown in Figure 2. The algorithm next tries the bottom path which results in a successful match. The problem with this algorithm is that it can result in an exponential runtime in the worst case when there are a very large number of paths through the NFA.

Figure 2: Checking whether the regex abab|abbb matches the string abbb using the back-tracking algorithm. Source

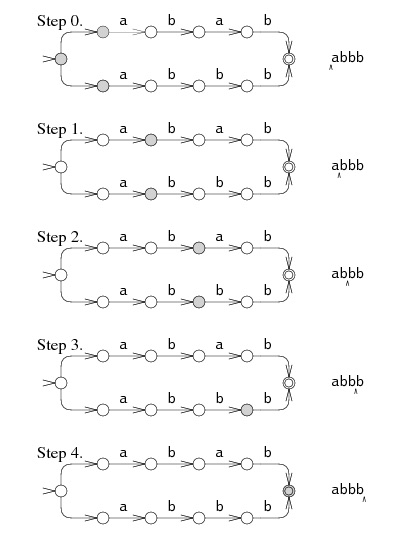

The second algorithm that Russ Cox discusses is based on a paper by Ken Thompson from 1968 and it allows multiple paths to be pursued at once. This approach is illustrated in Figure 3. In this case, the algorithm progresses along both paths in the NFA until Step 3 when the top path fails to match but it continues along the bottom path. The runtime for this algorithm is linear for even arbitrarily large input strings because it does not backtrack to the beginning in the case of a failed match.

Figure 3: Thompson (1968) algorithm for checking a regex match. Source

Regexes in Practice

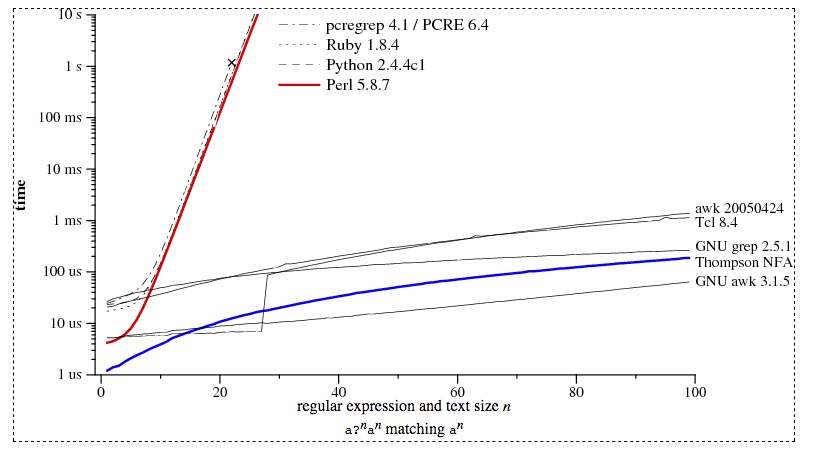

Figure 4 compares the performance of the regex libraries in some popular programming languages with the Thompson NFA algorithm. The relatively poor performance of the programming languages clearly indicates that they rely on backtracking instead of the Thompson NFA approach. This may seem puzzling. After all, if the backtracking algorithm can result in exponential runtime in some cases and the Thompson NFA algorithm avoids this, why would any library implement the former instead of the latter? The answer relates to the way that regexes are used in practice.

Figure 4: Comparing performance of regex implementations. The graph shows how long it takes for checking whether a regex of the form a?nan matches an as n grows. For example,with n = 3 it checks how long a?a?a?aaa takes to match aaa. Source

First, it is important to note that the exponential runtime for the backtracking algorithm only appears in what Cox calls “pathological” regexes. For example, consider whether the regex a?a?a?aaa matches the string aaa. In regexes the term ? matches zero or one of the preceding character and three ? terms means that there are 2^3 possibilities in this case and only the final possibility that the algorithm will try (zero for each of the ? terms) will result in a successful match. Thus this algorithm is O(2^n) which results in very poor performance for even reasonably sized n. However, the vast majority of the regexes used in practice are not so unlucky and do not suffer from such poor performance.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, Cox notes that regexes have evolved over time from the original Unix implementations and many new features require the use of the backtracking algorithm. One prominent example of this is the backreference. In the regex (abc)\1 the backreference character \1 means that we should match the characters in parentheses abc again so that this expression matches abcabc but not abc.

Trade-Offs

It would seem, then, that the developers of regex libraries face a difficult trade-off between the two algorithms. As noted above, many popular programming languages use backtracking. This decision presumably comes from accepting that the so-called “pathological” cases are so rare in practice that performance with backtracking will be acceptable in most cases and the risk of exponential runtime is worth the additional features that it can provide and that users have grown to expect.

However, there are other libraries that take a different approach. Many of Google’s core products, for example, use a library called RE2 that was developed at Google by Russ Cox and others and which is based on the Thompson NFA approach. In another blog post, Russ Cox shows why Google favours this approach using Google Code Search as an example. This service allows users to search through public open source code without downloading it using regexes. It could easily fall victim to denial of service attacks from malicious users submitting “pathological” regexes if backtracking was used.

Regexes are also widely used in monitoring networks for malicious activity and the volume of traffic in this area means that performance is an important consideration. For example, Hyperscan is a regex library used in this field that also does not use backtracking. This novel features of this library include support for multiple regex patterns at once and streaming input. These features, which would not be possible if backtracking were used, give it a significant performance advantage in many cases.

Conclusion

The algorithm used to check whether a regex matches a string can have a significant impact on its performance. Applications which cannot risk any exponential runtimes or where performance is critical in all cases should avoid the backtracking algorithm. On the other hand, applications which do not have such requirements are likely to benefit from the additional features that the backtracking algorithm can provide.