Tuning Spark Executors Part 1

I’ve used Apache Spark at work for a couple of months and have often found the settings that control the executors slightly confusing. In particular, I’ve found it difficult to see the impact of choosing the number of executors, number of executor cores, and executor memory and to understand how to manage the trade-offs between these settings. So I decided that I would run some experiments and document the results to improve my understanding. In this post I will briefly discuss what each of these executor settings control and show simple examples of how they affect performance.

Cluster Setup

I decided to use the Google Cloud Platform Dataproc service to launch a cluster to run the experiments on because it offers a relatively quick and easy way to launch a cluster with Spark and Hadoop. I chose a three node cluster with 8 cores and 32GB of memory each. Assuming that you have setup the Google Cloud SDK correctly you can launch a similar cluster using the following command:

gcloud beta dataproc clusters create standard-cluster --max-age="6h" --worker-machine-type=custom-8-32768 --num-preemptible-workers=1

spark-bench

During my research for this project I came across an interesting library called spark-bench for running Spark benchmarks. This project allows users to test multiple Spark settings easily by using a simple configuration file. One of the Spark jobs (called workloads) that spark-bench offers as an example is SparkPi which estimates Pi in a distributed manner. I decided to use this workload to run my initial estimates.

num-executors

Executors are one of the most important parts of the Spark architecture. These are the processes that actually run computations and store data. Many newcomers to Spark (including myself) try to improve Spark performance by simply increasing the number of executors and in some cases this improves performance by using more of the cluster resources. We can test the effect of increasing the number of executors from 1 to 5 using the spark-bench config file below:

spark-bench = {

spark-submit-config = [{

spark-args = {

num-executors = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

}

conf = {

"spark.dynamicAllocation.enabled" = "false"

}

workload-suites = [

{

descr = "One run of SparkPi and that's it!"

benchmark-output = "hdfs:///tmp/benchmarkOutput/full.parquet"

save-mode = "append"

repeat = 5

workloads = [

{

name = "sparkpi"

slices = 10000

}

]

}

]

}]

}

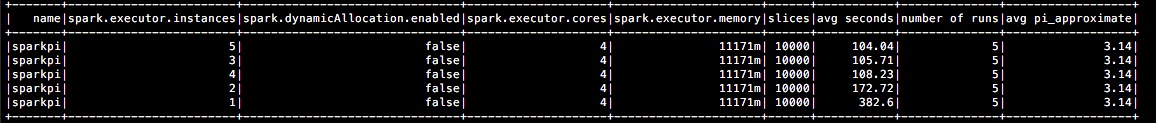

This config files means that the SparkPi workload will be run 5 times separately with the num-executors setting in the spark-submit config ranging from 1 up to 5. For each num-exeuctor setting I ran the workload 5 times (controlled by the repeat parameter in the config file) and averaged the results. The averaged results are shown in the table below:

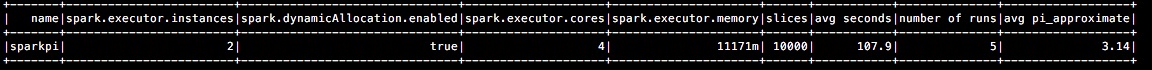

As show in the avg. seconds column, the workload generally takes less time as we increase the number of executors, although there is little difference after we reach three executors. However, the introduction of dynamic allocation from Spark 1.2 onwards has made choosing the number of executors less important. This setting, which can be controlled from the spark-settings file, allows the Spark application to automatically scale the number of executors up and down based on the amount of work. In practice, executors are requested when there are pending tasks and are removed when idle for a certain period. To show the impact of dynamic allocation in practice I ran the same job as above but with the number of executors set to 2 and dynamic allocation turned on. If we compare the case where we have two executors without dynamic allocation above to the results below we can see that turning this setting on improved performance in this case:

The Spark UI Event Timeline shows that our request for two executors is ignored and additional executors are added over time.

Even though this setting is useful for automatically controlling the number of executors it does not affect the number of cores or the memory in the executors so it is still important to consider these settings.

executor-cores

On each executor in Spark there are a certain number of cores. These are slots that we insert tasks that we can run concurrently into. The executor-cores flag in spark therefore controls how many concurrent tasks an executor can run. To test the impact of increasing the number of executor cores I added the settings below in my spark-bench config file. For simplicity I set the number of executors to 3 so that each node in the cluster has 1 executor and set dynamic allocation to false to keep the number of executors fixed:

spark-bench = {

spark-submit-config = [{

spark-args = {

executor-cores = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

num-executors = 3

}

conf = {

"spark.dynamicAllocation.enabled" = "false"

}

workload-suites = [

{

descr = "One run of SparkPi and that's it!"

benchmark-output = "hdfs:///tmp/benchmarkOutput/full.parquet"

save-mode = "append"

repeat = 5

workloads = [

{

name = "sparkpi"

slices = 10000

}

]

}

]

}]

}

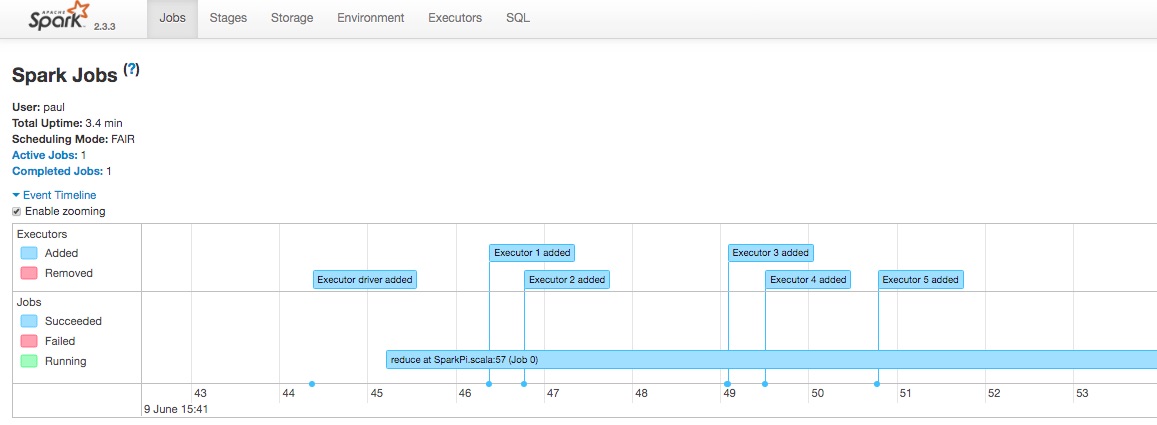

The results are shown below:

Surprisingly, the performance seemed to deteriorate when more cores were used for each executor. The reason for this seems to be that the random function in the standard SparkPi implementation can’t scale to multiple cores and so is not a good test of Spark performance as outlined in this StackOverflow question. To overcome this problem I decided to write a slightly modified SparkPi implementation called SparkPiConcurrent which uses a random function that doesn’t suffer from this drawback:

case class SparkPi(input: Option[String] = None,

output: Option[String] = None,

saveMode: String = SaveModes.error,

slices: Int

) extends Workload {

// Taken directly from Spark Examples:

// https://github.com/apache/spark/blob/master/examples/src/main/scala/org/apache/spark/examples/SparkPi.scala

def calculatePi(spark: SparkSession): Double = {

val n = math.min(100000L * slices, Int.MaxValue).toInt // avoid overflow

val count = spark.sparkContext.parallelize(1 until n, slices).map { i =>

val x = random * 2 - 1

val y = random * 2 - 1

if ((x * x) + (y * y) <= 1) 1 else 0

}.reduce(_ + _)

val piApproximate = 4.0 * count / (n - 1)

piApproximate

}

...

}

...

case class SparkPiConcurrent(input: Option[String] = None,

output: Option[String] = None,

saveMode: String = SaveModes.error,

slices: Int

) extends Workload {

def calculatePi(spark: SparkSession): Double = {

val n = math.min(100000L * slices, Int.MaxValue).toInt // avoid overflow

val count = spark.sparkContext.parallelize(1 until n, slices).map { i =>

val x = ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextDouble() * 2 - 1

val y = ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextDouble() * 2 - 1

if ((x * x) + (y * y) <= 1) 1 else 0

}.reduce(_ + _)

val piApproximate = 4.0 * count / (n - 1)

piApproximate

}

...

}

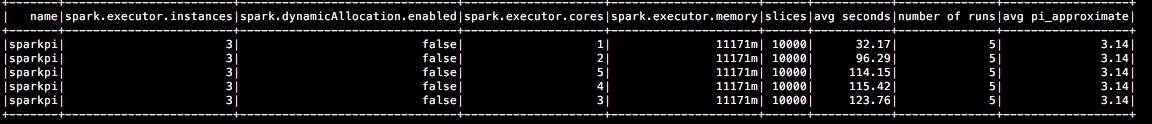

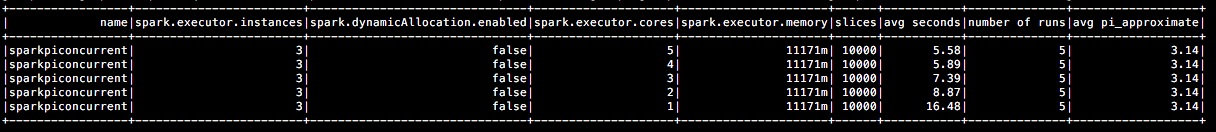

I ran the SparkPiConcurrent job using the same settings as above and this time the performance improved as more executor cores were used as expected:

For the remainder of this post and in the next post I will use the SparkPiConcurrent job to illustrate the performance implications of the other settings.

executor-memory

The executor-memory controls Spark’s caching behaviour and the size of objects when data is sent across the network. This setting is important because Spark jobs often throw out of memory errors when performing intensive operations. YARN can also kill an executor if it exceeds the YARN memory limits. On the other hand, running executors with too much memory can lead to delays with garbage collection. We have 32GB of memory available on each node in the cluster. In the config file below I keep the number of executors fixed at 3 and increase the amount of memory allocated to each as shown in the config file below:

spark-bench = {

spark-submit-config = [{

spark-args = {

executor-memory = [2g, 4g, 8g, 16g, 20g]

num-executors = 3

}

conf = {

"spark.dynamicAllocation.enabled" = "false"

}

workload-suites = [

{

descr = "One run of SparkPi and that's it!"

benchmark-output = "hdfs:///tmp/benchmarkOutput/full.parquet"

save-mode = "append"

repeat = 5

workloads = [

{

name = "sparkpiconcurrent"

slices = 10000

}

]

}

]

}]

}

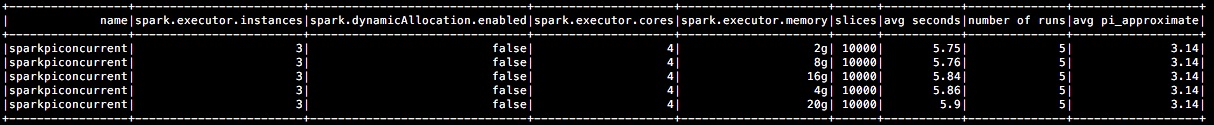

I was unable to increase the amount of executor memory much beyond 20GB without hitting YARN memory limits. Interestingly, increasing the executor memory seems to reduce performance, although the impact is quite small and probably not significant. This suggests that this particular job is not constrained by the amount of memory available on each of the executors:

Conclusion

In this post I’ve discussed some of the most important settings for tuning Spark executors and how to use the spark-bench library to test this. However, I have focused on each setting in isolation without considering how to optimise overall performance. To properly tune Spark executors it’s important to consider each of these settings together and in the next post I will show examples of how to do this.

All of the code to replicate the examples from these two blog posts are available on GitHub in my fork of the spark-bench library. Please feel free to contact me if you have any problems with the code.