Tuning Spark Executors Part 2

In the previous post I discussed three of the most important settings for tuning Spark executors and introduced the spark-bench library for performing Spark benchmarks. However, I only considered the impact of each of these settings in isolation. In this post I will consider how to balance the trade-offs between these settings using three examples. The three scenarios I present are based on this interesting talk at Spark Summit 2016.

Cluster Setup

In the Spark Summit 2016 talk linked to above the following cluster is used as a basis for all the examples:

The cluster I’m using is the same Google Cloud Platform Dataproc as in the previous post which has 3 nodes with 8 cores and 32GB of memory each so I have tried to adjust the examples accordingly. I will present three scenarios based on the Spark Summit talk and compare them with a base case which uses the default cluster settings.

Base Case

The spark-bench config file for the base case is shown below. This will repeat the SparkPiConcurrent workload discussed in the previous post 10 times with the default Spark settings for the Dataproc cluster.

spark-pi-base.conf

spark-bench = {

spark-submit-config = [{

workload-suites = [

{

benchmark-output = "hdfs:///tmp/benchmarkOutput/full.parquet"

save-mode = "append"

repeat = 10

workloads = [

{

name = "sparkpiconcurrent"

slices = 100000

}

]

}

]

}]

}

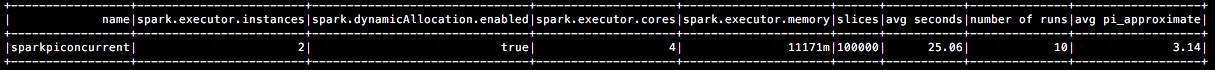

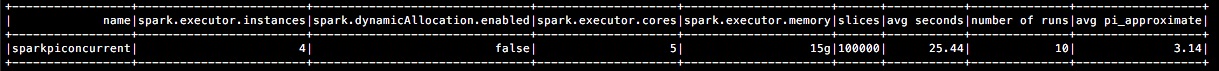

I take the average of the 10 runs and show the results below1:

Option 1: Most Granular (Tiny Executors)

The first option presented in the Spark Summit talk is to request a large number of executors each with low memory. Specifically, give each executor only 1 core which means that there will be 8 executors on each node and therefore each of these executors will get 32GB / 8 = 4GB of memory each. Each node has 8 executors (with 1 core each) so the whole cluster has 8 executors x 3 nodes = 24 executors in total. The spark-bench config file is shown below:

spark-pi-tiny.conf

spark-bench = {

spark-submit-config = [{

spark-args = {

num-executors = 24

executor-cores = 1

executor-memory = 4g

}

conf = {

"spark.dynamicAllocation.enabled" = "false"

}

workload-suites = [

{

benchmark-output = "hdfs:///tmp/benchmarkOutput/full.parquet"

save-mode = "append"

repeat = 10

workloads = [

{

name = "sparkpiconcurrent"

slices = 100000

}

]

}

]

}]

}

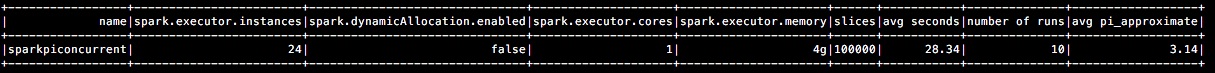

The results are shown below:

Note that even though 24 executors were requested a smaller number were actually delivered. This may be due to YARN memory limits or requirements to reserve memory for OS/Hadoop daemons.

Option 2: Least Granular (Fat Executors)

The problem with the first option is that it fails to make use of the benefits of running multiple tasks in the same executor. The second option goes to the opposite extreme. In this case we allocate 1 executor per node and give this executor as much memory as possible. I decided to give each executor 21GB of memory because I was unable to increase the amount of executor memory beyond this without hitting YARN memory limits. This single executor also uses all 8 cores available on each node.

spark-pi-fat.conf

spark-bench = {

spark-submit-config = [{

spark-args = {

num-executors = 3

executor-cores = 8

executor-memory = 21g

}

conf = {

"spark.dynamicAllocation.enabled" = "false"

}

workload-suites = [

{

benchmark-output = "hdfs:///tmp/benchmarkOutput/full.parquet"

save-mode = "append"

repeat = 10

workloads = [

{

name = "sparkpiconcurrent"

slices = 100000

}

]

}

]

}]

}

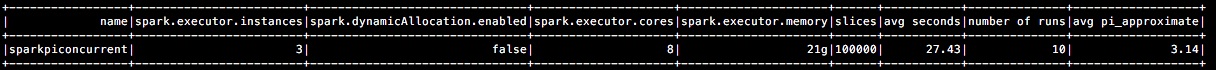

The results are shown below:

Option 3: Optimal Settings

The third option tries to achieve a balance between the two extremes presented above. First, as noted in the Spark Summit talk, the --executor-memory setting controls the heap size but we need to reserve some more memory for off-heap memory in YARN. Second, it is generally recommended to keep the number of cores per executor to 5 or fewer to improve HDFS I/O throughput. Finally, it is also recommended to leave 1 core per node for Hadoop/YARN daemon cores which leaves us with 3 x 7 = 21 cores in total in our cluster. We only want a maximum of 5 cores per executor which gives us 21 cores / 5 cores per executor = 4 executors (rounded down). We can allocate 15GB of memory to each of these 4 executors to ensure we are well within the YARN memory limits.

spark-pi-optimal.conf

spark-bench = {

spark-submit-config = [{

spark-args = {

num-executors = 4

executor-cores = 5

executor-memory = 12g

}

conf = {

"spark.dynamicAllocation.enabled" = "false"

}

workload-suites = [

{

benchmark-output = "hdfs:///tmp/benchmarkOutput/full.parquet"

save-mode = "append"

repeat = 10

workloads = [

{

name = "sparkpiconcurrent"

slices = 100000

}

]

}

]

}]

}

The results below show that this scenario offers an improvement over the previous two scenarios (lower avg. seconds) as we might expect. However, it’s quite interesting that it doesnt’t beat the default settings in the base case which suggests that the cluster settings are already quite suitable for this particular job.

Conclusion

In this post I have have discussed how to think about balancing the trade-offs between some of the settings for tuning spark executors. However, I have also shown that the default settings actually perform better in this particular job. This suggests that the default Spark settings are actually quite reasonable and offer a good starting point. It’s always important to remember, however, that there are many other spark settings that may have a much bigger impact on your job and which I haven’t discussed here. These include topics such as analysing data skew, checking the size of shuffle partitions, minimising data shuffles, etc.

All of the code to replicate the examples from these two blog posts are available on GitHub in my fork of the spark-bench library. Please feel free to contact me if you have any problems with the code.

-

Note that the results from this blog post are not directly comparable to those in the previous post because I’m using 100,000 slices in this post compared to only 10,000 in the previous post. The increase in slices effectively means that the estimate of Pi should be more precise so the examples in this post will take longer than in the previous post. ↩